Jul 2015 & Mar 2018Mind Uploading and the Question of Life, the Universe, and EverythingA shorter and slightly reorganized version of this paper was published by IEET in 2015. In 2018, I published the original, longer version below, and also as a PDF locally on this site.

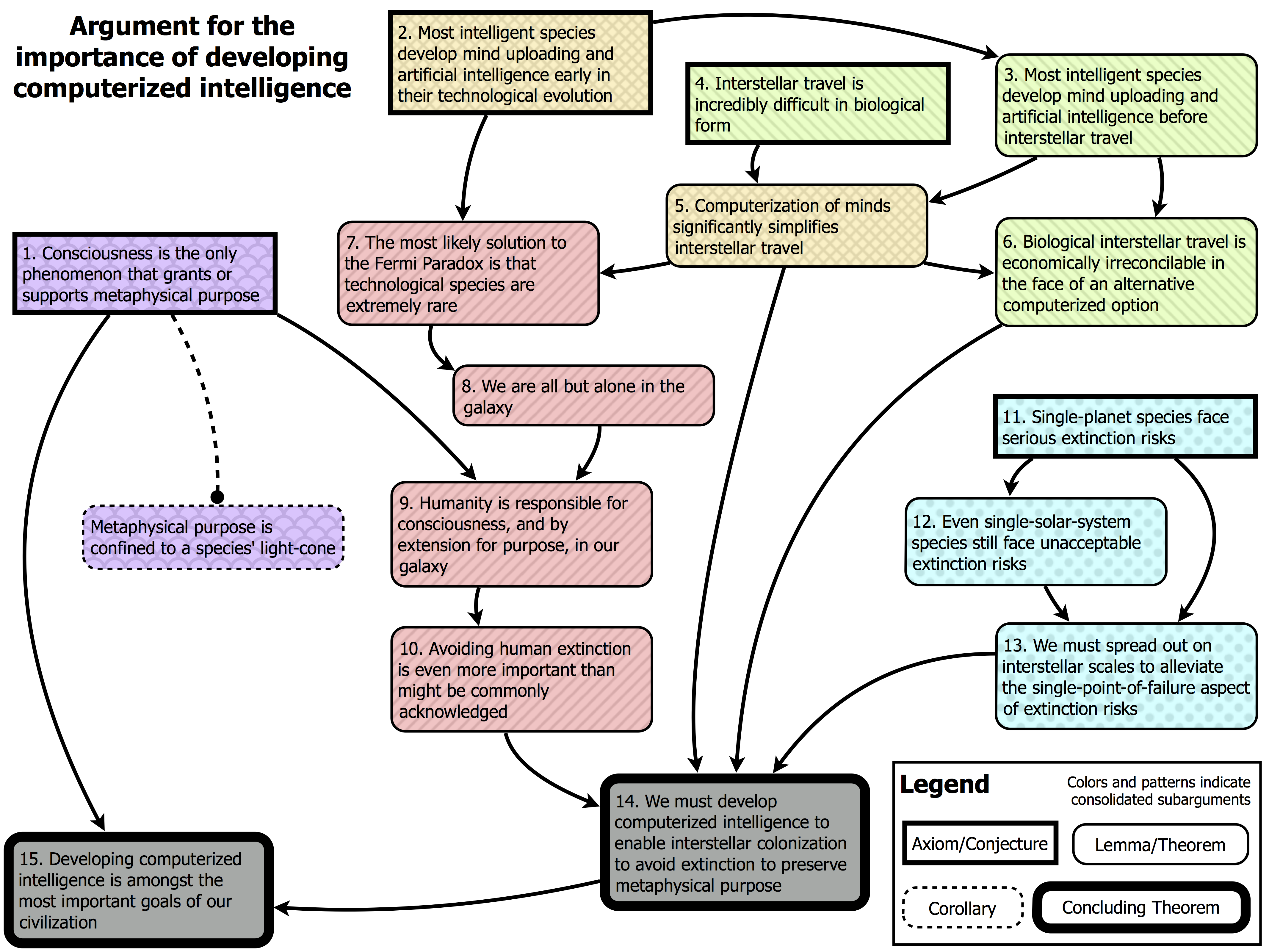

AbstractMind uploading is most often motivated by individual life extension. Other benefits and motives are generally considered only with secondary priority. We propose an alternative primary motive for pursuing mind uploading technology, that of perpetuating fundamental metaphysical purpose in the universe by preserving conscious minds from whom such purpose must derive. This approach lends the field of mind uploading—both scientific and philosophical—greater credibility by substituting grand civilizational goals for mere personal goals. Furthermore, this approach illuminates what should be the single greatest existential concern of any civilization and its conscious members: determining and then maintaining universal purpose over cosmological timespans. IntroductionOne of the most popular reasons to pursue mind uploading (MU) (Wiley 2014) technology is the desire for individual life extension, i.e., to mitigate otherwise inevitable impending biological death. Other reasons include enhancing intelligence, expanding the range of human experiences, curing neurological and psychological diseases, or enabling virtual reality with an otherwise biologically unachievable verisimilitude, but in truth, most introductions to the topic emphasize life extension. To some audiences, individual life extension may sound narcissistic and/or dismissive of more prosaic problems, like poverty. Additionally, when poorly presented, the topic can invoke fears of unequal access. While counterarguments can be raised against such concerns, another approach is to offer a different primary reason in the first place. As reasonable as it may be to empower people over their own death, such a goal does not implicitly serve any grander ambition, such as advancing civilization. A complete philosophy of life and of humanity should include such far-reaching aspirations. Toward that end, we offer a more monumental reason for the necessity of MU: that it is an essential stepping stone not only in establishing humanity's long term survival, but in guaranteeing that humanity, the universe, and even existence, all have a fundamental metaphysical purpose, essentially the cosmological extension of the individual notion of meaning of life. Metaphysical PurposeIn physics, the standard model includes the notion of fundamental particles and forces. The term fundamental implies that such particles and forces cannot be reduced to, or explained by, lower causal phenomena. They are essentially axiomatic to physical reality. In metaphysical philosophy, a similar concept is purpose: an independent, first-cause-like, inexplicable motive or reason for being that underlies some entity's existence, say that of a person, a civilization, a species, a cosmic locale (planet or galaxy), or the entire universe. Purpose might even apply to the abstract notion of reality (the fact that anything exists in the first place). This idea is also jocularly recognized in Douglas Adams' Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything (Adams 1979), from which we adapted this paper's title, and is captured by deep introspective questions such as "What is my purpose in life?" or "What is the meaning of life?". We propose that it is possible to define at least a partial form of fundamental metaphysical purpose, that of preserving conscious minds, and then further prescribe certain priorities stemming from that purpose, namely developing computerized intelligence (CI), either in the form of MU, or artificial intelligence (AI), or augmented intelligence (AugI) (in which the brain benefits from neuro-computational prostheses; in the limit, AugI would essentially converge on full MU). Extinction vs. Existential RiskThis paper's primary point comes down to avoiding either human extinction or other outcomes practically as bad as extinction. Extinction refers to the total vanishment of all members of a species. Comparably deleterious outcomes other than extinction are generally known as existential risks (Bostrom 2014). This article uses both terms somewhat interchangeably. Outcomes that may not represent extinction in the short term can be interpreted as delayed extinction in the long term. Examples include an unrecoverable collapse of our energy infrastructure (say if we deplete accessible fossil fuels before using the last reserves to power a transition to alternatives) or a ravaging by climate change that renders advanced civilization unrestorable. By failing to preserve a functional civilization, we are most likely dooming ourselves at a later time. Consequently, the distinction between extinction and existential risk is not crucial to the issues this article addresses. Computerized IntelligenceIn this article we frequently refer to computerized intelligence. This term indicates any of MU, AI, or AugI wherever one is not required over the others in a particular statement. However, MU generally offers the best advantages to the topics under consideration. MU and AugI can carry our individual selves forward, whereas AI does not preserve personal identity; one's values and desires must be handed off to the next generation of minds. Additionally, MU and AugI more effectively preserve the human condition, i.e., the uniquely human way of being intelligent and sentient. While AI developed on Earth is likely to better reflect human psychology than AI developed by extraterrestrial species, it is nevertheless further removed from humanity than MU or AugI. AI therefore does not maintain humanity's metaphysical purpose as effectively as the other two. On the other hand, MU and AI offer a different advantage, namely facilitating space travel, a crucial point of the argument we present in this paper. Since AugI has one advantage, AI has another, and MU has both, MU is the focus of this article. The ArgumentOverviewWe first present the argument in broad strokes and then examine each point in greater detail later. Each point is either a premise (marked with a 'P') or a conclusion from earlier points (marked with a 'C'). Here is the simplest presentation of the entire chain of reasoning. Figure 1 summarizes the argument, with premises indicated by sharp-cornered boxes, conclusions indicated by round-cornered boxes, and implications between boxes indicated with arrows.

Figure 1: Argument for the importance of developing computerized intelligence: This figure presents the argument for the importance of developing computerized intelligence in the form of a theorem of sorts. Initial claims (axioms) propagate lines of reasoning through intermediate claims to the two concluding statements at the bottom. This figure is essentially synonymous with the version of the argument presented in the text in list form. Argument with Brief ExplanationsIn this section, each point of the argument is offered with a brief explanation. Later, some of the points are scrutinized in greater detail. Additionally, later sections consider how the overall argument would be affected if individual points were weakened or entirely negated. Note that references are minimal in this section, the bulk being left to the later discussion.

SummaryDeveloping the technologies of CI, preferably MU although perhaps AI or AugI as well, is nearly the most important goal of our civilization. Notably, this line of reasoning makes no mention of the more common and unrelated reason for pursuing MU, that of extending individual lifespans. That is a personal goal, not a grand universal goal. We are concerned with insuring that the universe, reality, and existence preserve fundamental purpose. This goal is met by maintaining consciousness in the form of conscious beings who escape extinction and maximize their conscious experiences. We are further concerned with insuring that humanity retains its share of that purpose by preserving our species against extinction. The alternatives, that the universe and existence could lose ultimate purpose at a needlessly early cosmic hour, or that humanity might fade into obscurity, are too horrible to bare and cannot be allowed to transpire. Possible Challenges to the ArgumentWe have presented an argument which suggests that humanity should take responsibility for the metaphysical purpose of the universe and even for the purpose of existence itself. From that argument, we have concluded that developing CI is essentially the premiere goal of our civilization since it directly facilitates, and furthermore is a veritable prerequisite for, that responsibility. We now consider possible challenges to the argument, as well as the implications for the final conclusion should any individual steps and their lines of reasoning be successfully weakened or negated. C3: Implications if Interstellar Travel Precedes Computerized IntelligenceC3 is an important early step of the argument. We have presented it with only a weak relation to P2, relying primarily on external references for its support, namely our previous article on the central topic of C3. Furthermore, its line of reasoning follows multiple paths to the conclusion in C14, and therefore its diminishment could significantly weaken the overall argument. If interstellar technology (propulsion, navigation, component maintenance over long mission lifetimes, etc.) matures before CI, then we are unlikely to postpone our initial interstellar voyages on the expectation of eventual CI. Given the opportunity, we would likely embark in biological form without waiting for CI. For brevity, we cannot present our argument on C3 in the same depth as our existing publication on the same topic (Wiley 2011a). We encourage curious readers to see that paper for our full analysis. P4, C6: Implications If Biological Interstellar Travel is FeasibleThere is a history of agreement with aspects of P2 through C6. For example, Bradbury, Cirkovic, Dvorsky, Shostak, Dick, Davies, Rees, and Schneider have all expressed the idea that most intelligent species will transition from biological to computerized and robotic form before venturing into the galaxy (Bradbury et al. 2011, Davies 2010, Dick 2006, Rees 2015, Schneider 2015 (forthcoming), Shostak 2009). However, it remains a minority viewpoint in the public eye, as evidenced by the majority of science fiction and general speculation on extraterrestrial encounters. Even the DARPA/NASA 100 Year Starship project, an ongoing series of grants, conferences and symposia, prominently features human interstellar travel (DARPA & NASA 2011-2015 (ongoing)), although one might credit them for simply leaving all options on the table. What if human interstellar travel is ultimately feasible? For example, what if P4 is somehow alleviated and if C6 is consequently weakened due to its reliance on P4? A diminished C6 might enable us to pursue later conclusions (P10 and P13) without the need for CI. Notice that while weakening P4 does influence C5, C5 remains compelling from its other dependency on C3. Even if biological interstellar travel is feasible, the computerized alternative presented in C5 is still likely to be a net gain. Put differently, it is hard to imagine how interstellar travel could be explicitly harder in computerized form than in biological form. So, if CI arrives first, ala C3, biological methods remain economically impractical. In order to fully obviate C6 we must weaken both C3 and C5 and do so enough to actually undermine the claim in C6, not just weaken it. We would have to conclude that biological travel is still viable even in the presence of CI. Consequently, assuming both methods are available, merely weakening P4 or C6 a little bit shouldn't impact the overall argument. C7, C8: Implications If Intelligence is Actually CommonPeople frequently disagree with C7 and C8, the stance on the Fermi Paradox that intelligence is astoundingly rare in our galaxy (and the cosmos in general). To be clear, we are not making the strong claim that humanity is unique in the universe—merely that minds with human levels of versatility are far less common than is frequently assumed (others have reached similar conclusions similar, e.g. (Crawford 2000, Hart 1975, Kurzweil 2005, Paul & Cox 1996, Tipler 1980, Ward & Brownlee 2000, Webb 2002); see also our (Wiley 2011b) technical paper for a deeper analysis. Nevertheless, what if this claim is in error and there are reasonable solutions to the Fermi Paradox which permit a veritable cornucopia of intelligent and conscious species? Although few intelligence-optimistic responses to the paradox withstand critical scrutiny (Webb 2002), some responses are better than others. The transcension hypothesis (Smart 2012) is a tantalizing example (although like essentially all intelligence-optimistic responses, it faces the non-exclusivity problem (Dvorsky 2007), namely that it must apply to practically every intelligent species to arise in the cosmos—or at least in our galaxy—to resolve the paradox). How might an intelligence-abundant cosmic state impact the overall argument? It would admittedly salvage metaphysical purpose on universal scales, since it would provide a plethora of conscious beings, civilizations, and species to carry the torch of purpose, thereby lessening our burden in that respect—but perhaps we have additional goals. Perhaps our desire should not merely be that purpose survive at all, but furthermore that humanity have the opportunity to play an active role in that purpose. Thus, not only might the universe preserve purpose through consciousness, but so may humanity preserve its little slice of purpose as well. Assuming one agrees that purpose should survive, it is entirely reasonable that humanity have some influence over that grand purpose. We can extend this reasoning to individuals. Although our primary goal is to offer an alternative to individual life extension as the common motive for mind uploading, one reason a person might nevertheless wish to remain alive is to claim his or her metaphysical purpose, to put his or her stake in the sand and proclaim "I was here, and my life had a nonzero impact on the fate of the universe!" In this way, each person can play a causal role in cosmic destiny. P11, C12: Implications if Extinction Risks Are ExaggeratedSome people might claim that P11 and C12 are based on an unfounded premise, that human extinction or obsolescence is not a serious risk in the first place. Of those who do agree it is unacceptably risky, many may not feel that settling Mars offers sufficient protection. While some risks could not easily spread beyond Earth (e.g., asteroid impacts, climate change, etc.), other natural risks could threaten the entire solar system in one fell swoop, such as gamma-ray bursts, nearby supernovae, or unfortunately aimed and spectacularly energetic coronal mass ejections. Admittedly, these risks present fairly low probabilities, and one might argue that we can dismiss them—but only to an approximation. The most dangerous extinction risks may be anthropogenic. A war on Earth could easily spread to other sites where the local population might take sides over the same disagreements. Self- destructive or stagnating memes, such as fundamentalism, disenfranchisement, or xenophobia could infect nearby societies. In fact, doing so would be the hallmark of an effective meme as Dawkins originally coined the term (Dawkins 1976). Some risks might even explicitly attempt to spread. For example, and with an irony that is not lost in the context of this article, a malevolent AI might intentionally attack targets not only on Earth but elsewhere in the readily accessible solar system. We address this later. These risks, which could infect the entire solar system, heighten the need to spread on interstellar scales. And lest the reader extend this reasoning to the risk of interstellar invasions, thereby undermining the point of interstellar dispersal, we have argued elsewhere that this is unlikely with our theory of interstellar transportation bandwidth (Wiley 2011b), which claims that there are significant resource and capability bounds on the ability of cosmically distant societies to affect one another. However, perhaps none of these dangers truly pose existential risks in the first place and P11 and C12 are just fear-mongering over mere nuisances, not serious risks. In response, we must consider cosmological timescales. The issue of concern is not limited to the next century or even the next millennium. This article is about protecting universal metaphysical purpose. We must insure the maintenance of consciousness for as long as the universe can physically support: millions, billions, or potentially even trillions of years. Many readers will simply balk at such spans of time; the concerns of a future so distant can seem totally impenetrable. But that is the nature of universal purpose. To take it seriously, we either embrace it in its full extent or we miss the point entirely. As a popular adage says, extinction is forever. Some might claim that the obscure concerns of a far flung future are not our problem. While we certainly would not presume to advise those sages who will arise in the adolescence of the universe; our present time nevertheless represents a critical bottleneck, quite possibly one of Robin Hanson's popularized great filters (Hanson 1998). Our current single-planet era is terrifyingly precarious. Our time has one responsibility to the future above all others: solving the single point of failure problem to insure there is a future at all. We do not have to worry about how civilization will pass its time in a billion years, but we do have to give that future the best possible chance of actually coming to pass. With the realization that cosmological spans of time are central to the issue, the only conclusion is that we must take minuscule extinction risks seriously. From this realization, it follows that we cannot dismiss P11 and C12 unless we can essentially erase their associated risks. The best way to thoroughly mitigate existential risks is to spatially spread apart as far as possible. Remaining in a single solar system, much less confined to a single planet, is a recipe for extinction on sufficiently long timescales. P11, C14: Additional Existential Risks Introduced by Pursuing Computerized IntelligenceA popular concern is that AI (and perhaps MU and AugI although they are discussed less frequently with respect to this particular threat) could itself pose a significant existential risk. This concern has received considerable attention in Hollywood depictions and has enjoyed a recent resurgence from futurists such as Joy, Musk, Hawking, Gates, Bostrom, and Russell (Bohannon 2015, Bostrom 2002, Bostrom 2014, Joy 2000, Mamiit 2015). By such reasoning, pursuing the prescription in C15 (a call for the development of CI), could actually exacerbate P11, or possibly even C12. Despite the advantage of alleviating single-planet and single-solar- system extinction via interstellar colonization, might we be better advised to avoid the risks associated with CI? A capitalistic, if somewhat cynical, response is that any state or nation that foregoes CI positions itself badly in the global market. Short of a world-spanning hegemony to enforce a prohibition against such work, it seems futile for one society to voluntarily cede that work to another. Some degree of vigilance is to be encouraged of course. Our argument is not against any reasonable caution, but rather against giving into petrifying fears. Since CI is critical to long term survival for the reasons we have presented, we must move forward, even as we acknowledge and take account of the challenges CI may pose. Another response to fears that CI actually increases existential risk emphasizes the primary motive of this article: to protect against all the other existential risks. CI abstinence will actually imperil us in the long run. Sequestering ourselves on a single planet or within a single solar system out of fear of CI doesn't just fail to address all the other risks, it explicitly exacerbates them by compounding the single riskiest factor: our single point of failure. Eventually, calamity will strike any localized civilization. If CI is a prerequisite for interstellar travel, then it must be given sincere consideration despite its risks. The reasonable prudence recommended by most of the speakers listed in the first paragraph of this section is usually overlooked in editorial summaries (as evidenced by the fact that Cameron and Hurd's Terminator is the prevailing accompanying image for such editorials). Having realized that his own words were being used in arguments against CI progress, Bostrom has clarified that he does in fact intend that CI be pursued (Cuthbertson 2015). Considerations of the future over spans not only of decades or centuries, but of millennia or even millions or years, require a recalibration of risk assessments. We propose that CI is our only chance at attaining long term survival. A single point of failure will eventually fail, P4 and C6 argue that biological interstellar travel is an unlikely alternative. Even if the biological options are barely possible, they will likely take much longer to develop, allowing additional time for other disasters to strike. P1, C14: Failure to Solve Existential NihilismExistential NihilismExistential nihilism is the philosophical stance that life or the world has no objective fundamental purpose, precisely the kind of metaphysical purpose that is the central focus of this article. Sometimes existentialism (or nihilism) distinguishes between applications to an individual person's life (the purpose of my life) and broader universal issues (the purpose of the universe or existence). Where such distinctions arise, this article concerns the latter, grander meaning of existence. The End of the Universe, Consciousness, and PurposeAdmittedly, attempting to preserve fundamental purpose might seem like a fruitless endeavor upon an all-encompassing analysis. After all, the universe is doomed—eventually, along with everything in it of course. We don't have room here to consider theories of how life might survive the end of the universe, so we will proceed with the more conventional view that it won't. We can therefore consider the actual moment in the far flung future when the last conscious being in the entire universe dies. This is not hypothetical, but rather an actual event that will inevitably occur by our current understanding. There is some specific instant carved into time itself when the last conscious being will physically die. When this final conscious event occurs, will the universe, reality, and existence then cease to have purpose since it will mark the end of the era of consciousness from which purpose could derive? SolutionsHumanity has handled existential nihilism in a variety of ways. By far the most popular solution is to invent supernatural escape hatches, such as eternal gods and eternal afterlives in which to forever perpetuate consciousness for reasons very similar to step P1, namely that consciousness is preeminent in the establishment and maintenance of purpose. Those for whom supernaturalism fails to withstand logical scrutiny must find other solutions. One common secular solution is to essentially ignore the problem by focusing on individual purpose, i.e., to all but deny the universal problem and emphasize individual purpose. We have nothing to say about the religious solution here. We prefer solutions that avoid supernaturalism. Alternatively, while we sympathize with the secular intent behind focusing on individual purpose to the demotion of universal purpose, such an approach honestly does not solve the greater problem; it merely avoids it (probably out of angst), and avoidance is not a solution, it is a denial. Denial is a violation against one's own realizations and is therefore deplorable. To thine own self be true. Sartre's Solution and a Proposed Universal ExtrapolationJohn-Paul Sartre said that existence precedes essence, i.e., that people are born with no preordained purpose and then are responsible for discovering or creating their individual purpose in the world, the meaning of their individual lives (Sartre 1957). We can extend Sartre's dictum beyond the individual. Our concern is with fundamental purpose, any purpose that we might conceive at the level of the universe, reality, or existence. Extended thusly, and if consciousness underlies purpose, the universe and reality are then necessarily born without purpose since at the outset they lack conscious members: Sartre would say the universe's existence precedes its essence. With the evolutionary arrival of consciousness, the universe then moves to the next stage, in which its purpose is discovered or created from within. We depart from Sartre at this point since the universe isn't conscious itself, so as to could take Sartre-like responsibility for its own purpose. Rather, with the arrival of conscious beings, we are then granted (or perhaps condemned as Sartre put it!) to determine the purpose of the universe, reality, and existence. This is a condemned freedom far beyond Sartre's initial intent at the level of the individual. We are so astoundingly, shockingly, horrifyingly responsible for the universe. Humanity, and you the reader in your small part, are directly responsible for universal metaphysical purpose. Camus' Solution and a Proposed Universal ExtrapolationAlbert Camus concluded that there is no fundamental meaning of life, but offered a solution to the problems this conclusion poses. We first honestly accept life's meaninglessness. He called this the absurd realization, later formalized as Camus' philosophy of the absurd (Camus 1961). Camus' offered a two-part approach to handling life in the face of the absurd conclusion that there is no fundamental purpose. The first part is to fully embrace the truth of the absurdity. In Camus' philosophy, this resignation is the ultimate triumph over the lack of fundamental purpose, where a failure would consist or refusing the absurd stance to begin with (see where we scorned denial a few paragraphs back?). This idea might be recast as celebrating rational acceptance of an undesirable truth over the preferable alternative of irrational denial and self-delusion. The second part of Camus' solution to the absurd is to revolt against it: to accept cosmic futility while refusing to accept the expected despair, or in his own words: "That revolt is the certainty of a crushing fate, without the resignation that ought to accompany it." Like Sartre, Camus contemplates the matter at the level of the individual. In response to the possibility that there can be no eternal metaphysical purpose we propose a similar approach, but extended to universal scale. This approach is similar to how we extended Sartre from the individual to the broader universe. We first admit that the only rational, if absurd, conclusion is that metaphysical purpose cannot exist in an eternal sense. But at the same time, we apply Camus' second step and revolt against despondency. We should strive for the greatest conceivable level of universal accomplishment, and in our current cosmic infancy there is so incredibly much to aspire to. Virtually all the possibilities and conscious experience lie ahead of us, not behind. Tremendous adventures lie in wait for those species that survive their fragile youth. This article offers the goal that underlies all other goals: the preservation of consciousness for as long as the universe can physically sustain. That is the highest existential calling for it enables all other desires, dreams, and actions. We hope we have impressed upon the reader that we are duty-bound by our own consciousness to undertake this quest with the greatest commitment and urgency. ConclusionIn some sense, we have not really resolved the problem of universal metaphysical purpose, specifically for the following reason. On the premise that purpose derives from consciousness, and on the fact that consciousness will inevitably eventually end, it would seem that eternal purpose cannot be salvaged. Our response is the only rational response we have found: to punt the question to future thinkers. This is not the same as the denial we railed against above. Denial is to refuse to acknowledge the validity of the question or the problem, or to substitute an easier but separate problem (such as disregarding universal purpose in favor of individual purpose). We don't deny the problem of eternal metaphysical purpose because we believe it is a real and currently unsolved question. However, we choose to focus on what can be done about it here and now. We exist at an inflection point. Earlier in Earth's history there was no consciousness on our planet of the sort we are considering here. Far in the future, assuming we survive, the risk of extinction (namely the risk of the vanishment of consciousness) will have been alleviated by spreading over vast cosmic expanses. Right now, we exist during the intermediate era, when Earthly consciousness exists, but tenuously so. We can be more temporally specific. While human consciousness has been around for millennia, it was only in the last century that we gained a sufficient understanding of cosmology to properly comprehend the potential for spreading out over cosmic distances. We refer to the discovery of the stellar main sequence, the nuclear fusion that powers stars, other galaxies and galactic group structure, galactic redshift (which characterizes how the universe evolves over time as well as informing us of the age of the universe), and many other factors salient to our modern understanding of the makeup of the cosmos. We often take our remarkable understanding of our place in the cosmos for granted, but none of these crucial properties the universe were known a mere hundred years ago. Many of the readers' own grandparents were born in a universe no larger than our galaxy. Likewise we are approaching that incredible historical juncture when interstellar travel will become technically feasible and we could therefore actually do something about it. Past generations could be said to have had the priority of avoiding extinction long enough to enable the great cosmic dispersal. In the same way, the priority of our time (or the very near future) is to act on that opportunity so as to insure the unimaginably long future that lies in wait. This is our highest priority since it determines whether there will even be any such future. We stand at the cusp of solving the extinction problem and thereby guaranteeing the fundamental purpose of the universe, reality, and existence by insuring the continuation of consciousness. This is a far grander calling than merely enabling individual life extension. Existential metaphysical purpose is our foremost responsibility as conscious beings, and CI is the method of achieving it. References

Adams, D. 1979. The hitchhiker's guide to the galaxy. Pan Books.

I would really like to hear what people think of this. If you prefer private feedback, you can email me at kwiley@keithwiley.com. Alternatively, the following form and comment section is available. Comments

|

|||||||||||||||||